Vacancy Tax in Malaysia: Should we or shouldn’t we?

The question of this new tax already weighs heavily down on many stakeholders

Contributed by Sulaiman Saheh

In other countries, the vacancy tax acts as a form of a deterrent on speculators.

It was reported on Aug 19 that the Minister of Housing and Local Government (KPKT) is currently formulating a tax that could be imposed on developers on their unsold properties, referred to as the Vacancy Tax, and it could be implemented as early as next year.

This movement was initially intended on developers who fail to sell their properties within six to nine months after its completion, hence preventing the overhang situation from further worsening.

Although the intention is to reduce the overhang property numbers, the implications of implementing the tax amidst a challenging period that Malaysia is in right now could have other widespread ramifications which were hotly debated by many stakeholders including economists, developers and consultants.

Seven days later, on Aug 26, the proposal was put on hold and was announced to be studied further after the Ministry had considered the feedback received under the current market conditions. So does this mean the practice of a Vacancy Tax in Malaysia is a matchmaking failure or is it that a different approach is needed for it to work?

Don’t jump to conclusions

Before coming to any conclusion, it is vital to understand what this form of taxation is based on, the conditions it is levied upon and how countries who practice such do so. As aptly named, a vacancy tax normally refers to a tax levied on properties that have been left vacant and unused for a period of time, as stipulated by the respective country’s laws, at a rate that has been set against the assessed value of the property.

It acts as a form of deterrent on speculators who purchase such properties to only reap the profit of price inflation without any intention of having the property used by either themselves or a tenant.

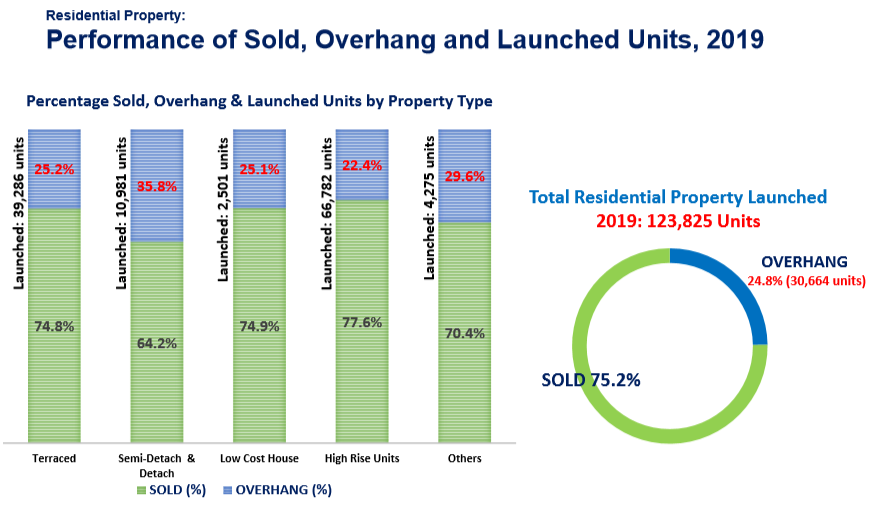

Figures show a breakdown of property types affected by supply outstripping demand: Can the Vacancy Tax stop the overhang?

This hoarding tendency has been seen amongst parties who are firstly, financially capable, and can be amongst property investors who intend to purely flip the property with no intention of occupation, as well as developers as reportedly seen in some other countries.

A vacancy tax seems to apply on the actual property not being used, occupied or tenanted after it is completed with proper certifications regardless of whether it was sold to a homeowner or still retained by a developer.

Other nation’s approach

In Canada, we see such tax being imposed at a city council level – like in the case of Vancouver City Council which applies the Empty Home Tax pursuant to the Vacancy Tax By-law; and, at the provincial level (akin to state-level) – like in the case of the provincial Government of British Columbia that applies the Speculation and Vacancy Tax.

In these cases, the vacancy tax applies to any vacant or unused houses subject to a set of prescribed criteria and condition, and the owners are to pay the tax, be it a homeowner or a developer holding to their unsold properties.

However, in Australia, where the regime is known as the Annual Vacancy Fee that is imposed by the Australian Taxation Office, the tax is only applicable to foreign owners who has residential dwellings that are not residentially occupied or rented out for more than six months in a year.

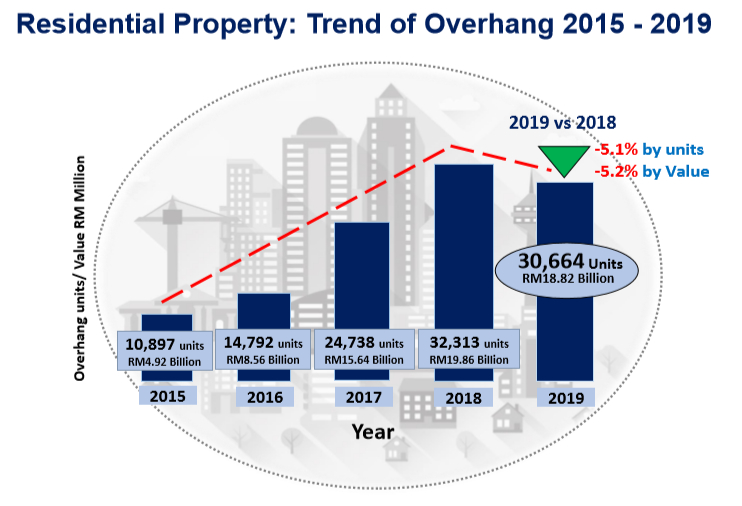

Year 2019 saw a dropped in the overhang due to the government’s Home Ownership Campaign.

In both countries, these regimes are their way of addressing home affordability issues whereby the intention is to increase the availability of rental housing amidst a housing market that is short in supply, thanks to speculation practitioners. For Hong Kong – where their version of the vacancy tax was proposed last year but was recently shelved due to insufficient time for thorough vetting of the bill, it was a measure against developers hoarding new units amidst a market of soaring prices.

Closer to home in Singapore, the Qualifying Certificate (QC) fee is imposed to ensure units developed are sold within two years of completion or face additional QC extension fees. On top of that, the Additional Buyers Stamp Duty is imposed to curb speculative purchases.

From these examples, it can be surmised that a vacancy tax is aimed to curbing hoarding habits for speculative reasons and opening intentionally empty homes out to the public who are in need of housing.

The Malaysian way

But when it comes to the Malaysian market, the situation is somewhat different whereby we are no longer in a soaring-price-market as how it was a few years back (although prices are still high compared to the average income levels resulting in low housing affordability).

Developers now find themselves in a position of having to bear the costs for holding the unsold units through assessments, maintenance charges, finance cost as well as physical deterioration to their inventories. It would be in the developers’ interest to sell those units quicker, of which we see that they have already begun reducing the effective price through rebates, discounts and other incentives to buyers.

Hoarding mentality

Instead of hoarding units away, developers are in need to make the sale before a unit is built before it is too late. But this inability to sell is not just about the property price alone, but also a function of the income levels, consumer sentiments and the attributes of the product itself – which opens up a whole new chapter of discussion.

We are looking at factors of oversupply and inaccessibility in housing that is beyond price related, which explains why 21.4% of the 48,619 unsold residential units (including serviced apartments and SOHOs) are within the affordable pricing range of below RM300,000.

Sulaiman Saheh is the director of research at Rahim & Co International, a global real estate consultancy firm.

And so in seeing the vacancy tax as a solution to Malaysia’s current market issues, it is unclear of the key objective of the proposed tax – whether it is a reactive measure to mend the current situation or is it a proactive measure to avoid gross imbalances in the future; or whether it is to tax developers who cannot sell the units that they have built so that they start to reduce prices to sell them off; or is it to increase supply in the rental market by imposing a tax to vacant units regardless of its ownership status, be it individual owners or the developers themselves?

Based on the emphasis stated by KPKT of their focus on developers and their persisting unsold units, it would be more appropriate and accurate to view this vacant-intent tax as an Unsold Property Tax instead. Though it is said to be against the spirit of free market, the unsold property tax does have its merit as a form of curbing overbuilding practices or hoarding activities to capitalise on speculative profits. Still, its relevance is dependent on the underlying problem.

Market still soft

In Malaysia, developers generally do want to sell their units and do not intend to hoard them – only that the current soft market makes it hard for the units to be sold. But should this be done prematurely, it can put further pressure on developers enough to force them into panic offloads – which may have other ripple effects.

Price may fall, which sounds good for the general homebuyers, but it could impact other existing house prices in the area and also on land prices, especially development land. Revaluations may give lower values, and as a result, banks’ mortgage collaterals and securities are impacted – and that may adversely affect the general consumers.

Listed companies, not just developers, may suffer from losses in property values – and this would have even further impact on the general economy, which is already soft. Rather, such a move would be more during a rising market and not in the challenging situation we find ourselves in right now – more so with the pandemic still dogging at our heels.

It has to be said that there is a need for independent market and feasibility studies to be done before any project is embarked or implemented. This would be a more implementable measure that should be done to minimise the risk of unsold units compounding into a gross oversupply in the market.

Ideally, the study should be conducted at the planning stage, but as the actual implementation date of the project may be at a much later date where the market may have changed, the study can be done as part of the submission for Development Order application or when applying for bridging loan or project financing.

Also of paramount importance is that the study must be commissioned independently – perhaps by the local authority or the banks – to ensure the objectivity of study outcomes.

Homework necessary

As the due diligence is conducted through an independent study by qualified professionals within the relevant sector, gaps can be identified to mitigate risks to the project’s viability.

However, the accuracy of the study is dependent of the availability of data and information, whereby cooperations from various parties like JPPH, DOSM, Local Authorities, banks and various agencies under different ministries and NGOs are needed.

The local authorities play a very important role. All future developments are monitored by the local authorities who then are in the position to monitor the overall flow of new supply assess its degree of suitability to the approved or gazetted City Plans/Local Plans and development densities designed.

Nevertheless, these studies are merely tools to forecast the project as no one can guarantee what the future holds. The objective is to take reasonable steps to mitigate the risks of unsold units that contribute to the overhang situation. Going back to the proposed tax in question – instead of shrugging the whole idea off entirely, this controversial tax regime may be more appropriate at different periods within the market cycle.

The controversial tax should be further studied and refined to have the desired effect.

It could be useful to discourage errant developers who just build without proper due diligence, even after imposing the requirement to conduct independent studies as suggested. The measure should be studied further and sufficiently refined to have the desired effect intended.

Furthermore, the implementation of any such tax proposal must consider the impact on existing approvals and under-construction projects which were embarked before the existence of the tax provision. Unfortunately, this would not address this current overhang problem. For existing projects, a different approach has to be taken so that unwanted adverse shocks are avoided, especially in an existing challenging environment.

The proposed tax needs a refined approach and clarity. If such a proposal is meant for taxing property owners who have left their units vacant by design or unable to find a tenant, then the regime would be a poor call. It is the right of an owner to enjoy the “Bundle of Rights” in its entirety of owning his or her property – and that includes the choice of leaving it vacant voluntarily or involuntarily as long as it is within the ambit of the law and does not cause detriment to anyone or any parties.

But in the matter of preventing future overhang numbers from worsening and effectively curbing irresponsible development plannings for profit’s sake, a vacancy tax can be well-matched with a more apropos name. But then again, one has to consider and balance any possible ramifications and match it with a clear and justful policy that has to be implemented in a timely manner.

Stay ahead of the crowd and enjoy fresh insights on real estate, property development, and lifestyle trends when you subscribe to our newsletter and follow us on social media.